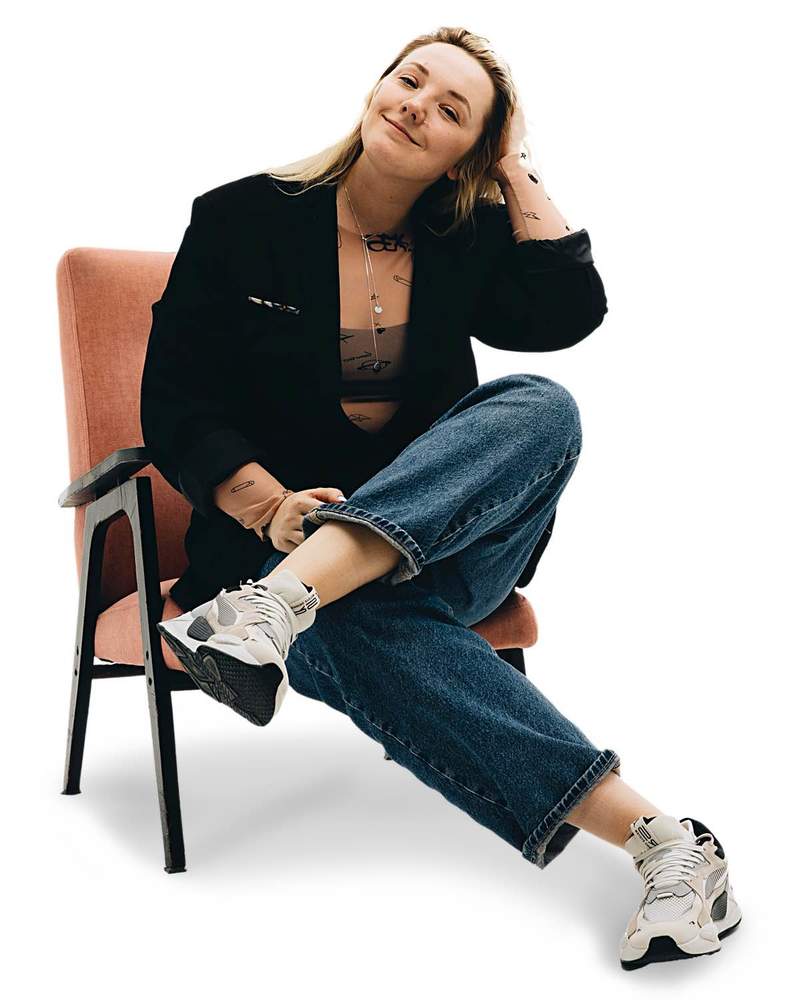

It seems like online dating and dating apps should have greatly simplified our lives. But in reality, technology simultaneously eases and complicates the search for relationships. How does the modern context (both technological and wartime) influence our romantic interactions, what relationship-related requests do clients most often bring – and how does psychotherapy work with them? We asked Treatfield therapists.

What has changed in recent years in how we date, meet people, and look for partners for relationships? From the perspective of dating app development and from the perspective of wartime.

Dating today has become something akin to placing an offer on a marketplace: simultaneously easier and harder than ever. Easier, because you have dozens of potential contacts, like buyers, in your pocket. Harder, because these contacts guarantee nothing but the illusion of comprehensive choice and ease of touch.

Dating apps have become a familiar environment for starting relationships. They've changed intimate geography: instead of chance encounters in cafes or at parties, we move between profiles, as if Browse a catalog. And while this model promises speed, it rarely offers depth. And this is a large space for illusions and projections. We meet "versions" of people and our fantasies about them according to carefully selected photos and descriptive texts that fit into the "About Me" field. There's nothing wrong with this either, it's just a different intimacy: not physical or empathic, but algorithmic and very often fantasized. And this is a large space for expectations and disappointments.

The war has further exposed the fragmentation of connections. Many have found themselves at a distance — geographically, emotionally, existentially. Some people are hesitant to invest in new relationships because the future seems fragile. Others, on the contrary, crave speed, intimacy here and now, without long preludes. Often exhausted, people don't want to choose a form of communication or "waste time." And the dance of getting to know someone, the awakening of interest, the birth of contact — all of this becomes functional, which prevents our feelings from living, and we lose vitality and pleasure from interacting with others. Relationships have become like tactical alliances: not always aiming for eternity, but with a deep desire to be not alone, even if formalized, for a little while.

The demand has also changed. If before people often looked for "someone ideal," now it's someone with whom they feel safe. People less often ask "does he/she suit me?" and more often "do I feel calm next to him/her?". In this, perhaps, there is more maturity than in all the "checklists of the ideal partner." But it's still worth asking yourself the question "am I here out of interest, out of excitement, or to share loneliness?" to be truthful with yourself. This will help build honest relationships and avoid entering into prolonged "not my own" partnerships.

Dating in wartime is like love against the backdrop of sirens. It's impossible to exclude the context, just as it's impossible to turn off the alarm. But even amidst uncertainty, someone is still creating Tinder pairs, looking for "someone just to talk to" at three in the morning, or traveling half the country because "something clicked."

Perhaps this fragile determination is the main thing about love right now. And what touches me most is that despite all the difficulties of the time, we still need other people.

What topics and requests, if they can be generalized, are currently most relevant for young clients regarding dating, romantic relationships, partner search, and acquaintances?

Today, clients aged 20-35 address deep and subtle questions about intimacy and autonomy, about trust and loneliness, about how to remain oneself in connection with another person. There is an increasing awareness that relationships are about constant choice and shared work.

Among the most common requests, I would include:

Experience or fear of codependency. Many have not experienced relationships where there was space for autonomy, sometimes this feels like losing oneself. In joint work, we work on its development — not as an escape from another person, but as part of healthy intimacy. The topic of personal boundaries also comes to the forefront here: where do I end and my boundaries, and where does the partner begin?

Lack of healthy models. A fairly large number of requests about not wanting to repeat the history of unhealthy family relationships, and at the same time — about the absence of alternative internal scenarios. "My parents had a terrible relationship. I definitely don't want that, — but I don't know how else." In therapy, this can be an invitation to explore and re-evaluate experiences and deep beliefs about relationships, intimacy, love, and roles in a couple that were formed in childhood. And subsequently, creating one's own views on these topics, taking into account personal values and needs.

The influence of past experience, unresolved past relationships. The body and psyche can hold on to past experience for a long time and even create an anxious expectation of repeating the past in new relationships. In our work, we focus on distinguishing between past and present, experiencing delayed emotions and feelings, giving oneself permission and space for new experiences. In other words, we complete the unfinished and restore a sense of security.

Questions of trust, shame for vulnerability. Especially when there has been past experience where trust = vulnerability = pain, it is important to find or build internal support. If I trust myself — I can open up to another, knowing that I won't break. The client-therapist relationship becomes a space for a new and gradual experience of openness and trust in a safe environment. Therapy helps reduce internal censorship on emotional self-expression, about which people can feel a lot of shame.

Tiredness from superficial acquaintances. This is often influenced by dating apps, which offer access to a large number of new faces in a short time, but, unfortunately, do not satisfy the need for genuine intimacy with a living person. In therapeutic work, it is important to explore authenticity, basic emotional needs, and ideas about social interactions.

Partner doesn't meet all my needs. This is a natural disappointment when encountering reality: there is no one person who should meet all your needs in adulthood. This moment opens the door to the process of maturation in relationships with others and to the development of an inner adult who can take care of themselves.

Fear of loneliness and abandonment. This is one of the deepest topics clients bring. In the therapeutic space, we also learn to endure loneliness not as punishment, but as a space for contact with oneself. And we work with deep beliefs and thoughts, process emotional memories, and reduce anxiety from being alone.

Misuse of psychological terms in everyday life. This is never a direct request, but it has a great impact on others mentioned above. When we call every second person a narcissist, toxic, or gaslighter, the term loses its meaning and attaches an incorrect label. We stop seeing a person as a person who is multidimensional, alive, and contradictory. This can be a form of self-defense — this method restores control and allows for distancing. But in the long run, it leads to even greater loneliness and alienation. In addition, it stigmatizes people with real personality difficulties.

How does psychotherapy work with the topic of finding a partner, difficulties in building long-term romantic relationships? How can psychotherapy help?

Dating today is more than just swipes.

It's about the fear of being unnoticed. About the hope that "this time will be different." About the fatigue of short dialogues that lead nowhere. About the question "What's wrong with me? Why can others do it, but I can't?"

It's attempts to say: "I'm open. I'm ready to meet," but at the same time fear that as soon as someone gets really close, you'll lose your voice.

Psychotherapy doesn't find you a match. It doesn't write perfect Tinder bios for you or give you a list of "5 topics for a first date." But it gives something else — often more important.

It helps you notice:

who are you looking to meet?

what do you bring to these relationships?

why do you suddenly become smaller than you are next to someone?

why do you choose those who don't choose you?

why do you cling to those who don't hear you?

and why does it hurt when others leave, even if you didn't really want them before?

In therapy, we look together: what old stories do you take with you on new dates? How do past rejections, betrayals, or devaluations still affect how you open up today?

Another truth about dating now — what is often shameful to admit even to yourself. Due to the war and prolonged exhaustion, many people lose what usually keeps us moving — impulse. Sometimes there's enough strength for a swipe or "hello." But as soon as it comes to a real meeting — there's no energy left. Not because you're lazy or "not like that." But because any contact is a step into the unknown. It's a risk. It's frustration and a live encounter with another and with who you are next to another. And all this requires resources.

Building relationships means having something to meet another person with: with curiosity, openness, space for live dialogue, for conversations — honest, different, sometimes uncomfortable. And many people today simply don't have the strength for this — and that's no reason to be ashamed. It's a reason to take a little more care of yourself than usual.

Sometimes therapy is a step that helps restore impulse — to life, to meetings, to relationships. First — with oneself. Then — with others.

Therapy is a place where you can learn to be in intimacy.

Where you can say without shame: "I'm scared. I'm sad. I want to be with someone, — but I'm afraid to lose myself." There you can learn to stay close to yourself, — even when you're next to someone else. Learn to hear your "want" and "no." Learn to leave what is not yours. And notice those who see you — real.

Therapy doesn't promise ideal relationships. But it can make it so that next time you go on a date not with a hole inside that someone has to fill, but with yourself — alive, interesting, and already sufficient.

How have modern mobile dating apps affected dating practices and partner search?

Disclaimer: The information in this material includes the results of modern research aimed at assessing the impact to prevent the negative consequences of online dating. This information cannot be used for self-diagnosis, diagnosis and/or treatment. For diagnosis and treatment, it is recommended to contact specialists.

Online dating has been popular since its inception in 1995, when the first dating site Match.com appeared. And dating apps in 2025 already have 337 million users worldwide. Satisfaction levels in couples who met through apps are comparable to those who met face-to-face — at least in studies among students and young adults. There is also data that in Switzerland, couples who met online show a greater intention to live together and have children than those who met offline.

The transformation of dating through mobile apps not only changes the way people meet, but profoundly affects the types of relationships that form and the psychological dynamics in these connections. For example, apps can reinforce dependent and codependent dynamics in relationships (match/unmatch reinforce the fear of abandonment; ghosting activates fears of losing control; often an attachment forms not to the person, but to the attention they give). Or even contribute to the creation of pseudo-relationships (connections that mimic romantic intimacy but lack a stable foundation: no agreement, plan, or responsibility).

And despite the growing popularity of dating apps, more and more studies show that "mobile dating" can also have a negative impact on various aspects of users' lives, and as a result — worsen the quality of life and relationships.

Next, I propose to consider different levels of impact of dating apps and their probable consequences for relationships between people.

Impact on hormone levels

The proliferation of relevant apps has led to a phenomenon that researchers have called the "dating app effect."

This term describes the phenomenon when users "experience dysregulation [of cortisol and dopamine] to such an extent that it resembles chronic stress disorder and addictive behavior." Hormonal imbalance is a result of the apps' impact on the brain's reward system. Essentially, when users find a match or engage in positive interactions, it can over time create an unhealthy "reinforcement schedule" and lead to neurochemical addiction.

Psychologically, the mechanism is similar to gambling: it's impossible to predict the "win" (achieving a match), and this subsequently leads to "seeking behavior." Addiction to this cycle means that the inability to use the app for a long period causes low mood, irritability, and even anxiety, as people crave the reinforcement schedule.

The use of dating apps can also affect testosterone and cortisol, influencing libido and thyroid function. In turn, this can cause a wide range of symptoms affecting metabolism and energy levels.

How all this can affect relationships (given a certain personality type):

Growing desire for novelty — partners quickly become boring.

A person starts constantly looking for "better" — even while already in a relationship.

Real connections feel boring compared to the app's drive.

Increased anxiety, control, need for constant validation.

Increased sensitivity to rejection and decreased ability to experience difficulties or tension in a couple.

Decreased self-trust and trust in a partner, as a result — reactivity arises: jealousy, resentment, alienation.

Impact on body image perception and overall well-being

According to 45 studies published between 2016 and 2023, significant negative effects of dating app use on body perception were reported (general satisfaction with body shape and/or size, dissatisfaction with skin tone, negative evaluation of appearance entirely or its individual parts). This is explained by the unique features of mobile dating apps, particularly the predominance of visual content and the ease of viewing multiple profiles. Unlike online dating websites, profiles in some apps are initially limited to visual content, and a short bio is only available after clicking on the profile. That is, physical attractiveness is likely a key factor in initial reactions and profile evaluations.

Expecting such close attention to appearance, users potentially risk self-objectification. Increased attention to appearance and body image can, in turn, lead to body dissatisfaction and anxiety about appearance. This can have a potentially negative impact on mental health.

The authors of such studies recommend that app developers look for ways to mitigate their harmful effects (e.g., reducing the role of visual content, time limits, user psychoeducation).

How this can affect relationships:

Gravitation towards object-relations rather than subject-relations (the partner is literally a certain "trophy" rather than a living person with their own needs and boundaries).

Decreased self-sensitivity due to excessive preoccupation with flaws (can lead to neglect of one's own needs, boundaries, loss of self-respect).

Increased shame, which will limit expressiveness (orientation towards thoughts about how to "properly" behave in relationships; control instead of the question "how do I feel in this relationship?").

Decreased / inability to feel satisfaction in relationships due to constant anxiety about appearance.

Avoidance of intimacy due to shame.

New challenges regarding safety, risks of victimization, and violence

The use of dating apps by adolescents is a new problem. An international survey of Finnish, American, Spanish, and South Korean students showed that 15% of adolescents use dating apps at least occasionally. Previous studies, which mainly surveyed young people, found that the use of mobile dating apps creates risks related to privacy, security, intimacy, victimization through sexting, sexual violence, risky sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Therefore, the urgent issue becomes psychoeducation for adolescents and adults regarding safety in the online space to prevent traumatization and other negative consequences.

Artificial intelligence — a new participant in love triangles?

The Washington Post published several accounts from mobile online dating app users about how they were captivated by communication with several users, and then during live dates "it was as if they were next to a completely different person." And these are stories not about a "Tinder swindler," but about the use of artificial intelligence in communication.

In comments on these stories, people condemned the generation of messages using AI, as such actions were misleading and created a false impression, leading to the undermining of authenticity and interpersonal communication skills. Some subscribers of the publication were concerned that AI could exacerbate problems of deception and misrepresentation in online dating.

Sources used, or What to read on the topic:

Learn more about the impact of dating app use on hormonal regulation: https://www.mirror.co.uk/lifestyle/dating/swiping-...

Read the full study on the impact of dating apps on body image perception and overall well-being: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/...

Read the full study on the risks arising in dating apps: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/13/11/903